When Mars and Berkshire Hathaway acquired Wrigley for $23 billion in the depths of 2008, most observers saw opportunism. What they missed was decades of patient preparation meeting its moment.

The companies that move fastest during crises are those that have moved slower before. While leveraged buyers retreat at the peak of fear, the few private and public companies that have hoarded cash can act decisively. In both the global financial crisis, and covid, Berkshire deployed billions in days while others scrambled for months. JPMorgan absorbed failing banks over weekends in the GFC when competitors couldn't move at all.

The difference between those who could move and those who couldn't came down to a fundamental understanding that business operates on multiple timescales and mastering this arbitrage enables speed and durability in scaling equity value over time.

To understand how patient preparation creates decisive speed, I'll show you three different maps of the same territory I've found practical.

Pace layers reveal where to be patient and where to be urgent, showing how businesses operate across multiple timescales simultaneously, from seasonal fashion to generational culture.

S-curves illuminate when those layers will hit their inflection points, helping you recognize which growth curve you're actually betting on.

Trust as a leading indicator - what emerges from ongoing interactions across and between layers (employees, communities, customers and processes), the invisible asset that compounds for decades.

These aren't separate but different lenses for viewing the same phenomenon. Together, they form an understanding of a system's natural rhythms, timing your moves to them and building the relationships that let you move faster when the moment arrives making time your friend as an investor and business operator.

Understanding the Pacing

"The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think." - Gregory Bateson

I like Stewart Brand's pace layering framework for understanding how businesses operate across time. It reveals why this matters so profoundly. In most complex systems, different elements change at different speeds. Fashion moves seasonally, commerce shifts yearly, infrastructure evolves over decades, governance changes generationally, and culture moves so slowly it appears frozen in time.

Think of a forest ecosystem. The Fashion layer is the wildflowers and seasonal foliage - changing with each season, immediately visible, responding to every shift in weather with a high rate of growth, and death which we all know. Commerce is the understory shrubs and small trees that grow, fruit, and regenerate over years. Infrastructure is the mature canopy trees that take decades to establish but create the conditions for everything below - providing shade, dropping nutrients, sheltering the system. Governance is the mycelium network underground - the fungal web that invisibly connects every plant, determining who gets resources and how the forest responds to threats. Culture is the soil itself - built from centuries of fallen leaves and decomposed life, so stable it seems permanent, yet its richness determines everything that can grow above.

Layers don’t exist separately, they form a single, interconnected living system which is sometimes hard to see. We tend to see layers as independent parts to optimize separately, but in living systems, layers are how the whole organism breathes - each rhythm nested within another, each movement part of a larger dance. The fast movements at the surface and slow currents in the depths aren't separate phenomena but the system's way of being alive at every scale simultaneously. Speed doesn't come from stability - they arise together from the coherence of the whole system.

But what does this mean when evaluating durable businesses?

When Zara pivots their clothing styles monthly, it's not despite their supply chain infrastructure - it's because that infrastructure has evolved over decades to enable precisely this rhythm.

When Stripe ships hidden features daily expanding their moat, they're not working against their platform architecture - they're expressing what that architecture was refined to accelerate hidden from the eyes of consumers over the next 50 years.

Apple master this temporal arbitrage. New iPhone colors arrive every season to satisfy the fashion layer, while annual product cycles drive the commerce layer with reliable predictability. But the iOS ecosystem, which represents their true competitive moat, took twenty years to build in the infrastructure layer, creating switching costs and network effects that compound with each passing year. Their App Store governance evolves with glacial deliberation, each change carefully considered for its long-term implications, while their design philosophy - the cultural layer that infuses everything they create - hasn't fundamentally changed since Jobs articulated it decades ago. You just have to look at their cumulative cash reserves to see whether they have the capacity to keep it up or not.

Competitors try to destroy Apple's fashion layer moat and assume that's the game being played. They miss the insight that Apple's speed in the fashion layer comes from stability in the infrastructure layer, that the layers aren't independent but deeply interdependent, with the slow layers enabling the fast ones to move with confidence and clarity.

Most businesses fail because they try to force all these layers to move at the same 'optimal' speed - usually quarterly in public markets. No matter how many times I watch a waterfall I can’t seem to ‘optimise’ the flow, but give me an excel model and its like magic!

Recognizing Which Growth Curve You're On

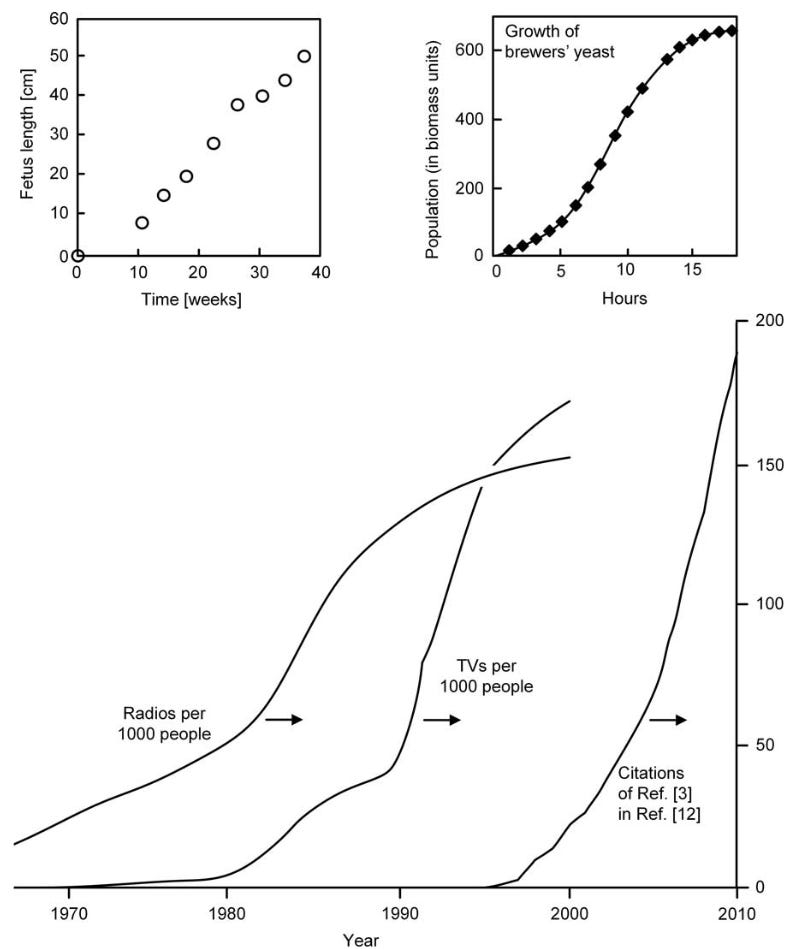

Every system in nature follows a predictable pattern of growth - slow beginnings, explosive middle, inevitable plateau. Scientists call this the S-curve, and it shows up everywhere: in how fetus length increases over weeks, how yeast populations expand in hours, how technologies spread through societies over decades.

What these curves reveal is profound. Nothing grows forever at the same rate. Every growth story (biological, technological, or business) follows this similar pattern. The grinding early phase where progress feels invisible. The explosive middle where everything compounds. The mature phase where growth slows due to a constraint and the next curve must begin. I would recommend checking out this talk by Geoffrey West.

Every founder knows this idea in their bones - the grinding early days when nothing seems to work, followed by that magical inflection point when everything clicks, and finally the inevitable plateau when growth slows and the next 'mountain' emerges.

But here's what most miss. In business, you're never riding just one S-curve. You're managing a portfolio of them, each operating at different speeds across different layers of your organization. Your product adoption might be hitting exponential growth (measured in months) while your infrastructure build-out is still in early grind (measured in years) and your culture formation hasn't even begun its curve (measured in decades).

Each layer experiences its own S-curve lifecycle, but at radically different speeds. Fashion trends hit their inflection points in months, commerce models in years, infrastructure in decades. The strategic advantage comes from recognizing you're not managing one S-curve but an entire portfolio of them, each nested within the others like Russian dolls. When leaders understand this, they stop asking "where are we on the S-curve?" and start asking "which S-curve in which layer?" a far more powerful question.

Netflix understood this with brutal clarity. In 2010, they were shipping 2 million DVDs daily - a massive operation at the peak of its S-curve. But Reed Hastings saw streaming was at the bottom of its S-curve, barely functional, with terrible selection and constant buffering. While Blockbuster optimized their mature retail model, Netflix deliberately cannibalized their profitable DVD business to ride the next wave. They moved $200 million from DVD operations into streaming content when streaming represented less than 20% of revenue. Today Netflix is worth $240 billion; Blockbuster is a cautionary tale.

Microsoft's transformation tells a similar story. In 2014, PC software licensing - the business that built their empire - was plateauing. Satya Nadella recognized that cloud computing, despite being a distant third to Amazon and Google, was still early in its S-curve. He bet the company on Azure, shifting from packaged software (mature S-curve) to cloud services (early S-curve). Wall Street hated it - margins dropped, revenues shifted, the model looked broken. But Nadella saw the curves: one dying, one being born. Azure now generates $60 billion annually and drives Microsoft's $3 trillion valuation.

Each exemplified the same principle: recognizing which S-curve you're actually on, having the courage to jump curves before it's comfortable, and building the capabilities in slow layers that enable fast execution when the moment arrives. The best capital allocators and leaders I worked with over the years are deeply intuitive in this.

Patient Capital in Practice: Kerry

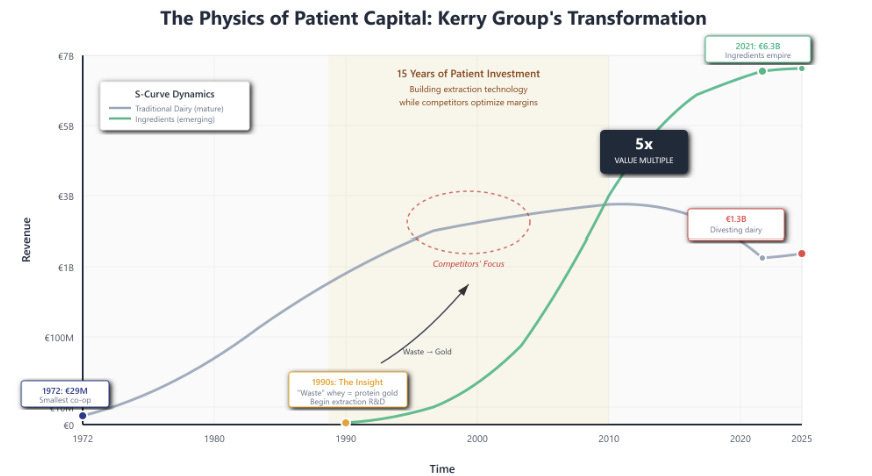

Kerry Group's transformation from Ireland's smallest dairy cooperative to a €6.3 billion ingredients empire illustrates how patience creates opportunities invisible to those focused on shorter horizons. Every dairy producer faced the same challenge with whey, the protein-rich liquid left over from cheese-making that represented both a disposal cost and a compliance headache. While the entire industry treated this as expensive waste, Kerry's leadership recognized something profound: they were looking at two different S-curves operating on completely different timescales.

The dairy business that consumed everyone's attention was approaching the top of its S-curve, with margins thinning and consolidation inevitable, while the ingredients business hadn't even begun its exponential climb. For fifteen years, Kerry invested in extraction technology and scientific capabilities while competitors focused on optimizing dairy margins. By the time health consciousness and specialized nutrition exploded into mainstream consciousness, Kerry had spent two decades perfecting protein extraction, understanding molecular structures, and building relationships with food manufacturers who needed exactly these capabilities.

This is where S-curves and trust intersect in profound ways. Kerry Group's fifteen-year investment in "waste" built credibility with food manufacturers long before the nutrition boom. They became the trusted partner who understood protein science when everyone else was still learning the vocabulary. Today they're divesting that original dairy business entirely because the waste stream became worth five times more than the original business. This is patient capital's hidden physics - not accepting lower returns for some vague future benefit, but building tomorrow's high-return capabilities while others optimize yesterday's increasingly commoditized business.

Patient Capital in Practice: BYD

BYD's path to becoming the world's largest electric vehicle manufacturer tells the same story through a different lens. While Tesla captured headlines and traditional automakers scrambled to electrify existing platforms, BYD spent twenty years as a battery manufacturer, accumulating deep understanding of energy storage at the molecular level. They mastered lithium iron phosphate chemistry when everyone else chased lithium-ion performance metrics, accepting lower energy density in exchange for better thermal stability and longer cycle life.

When they finally entered vehicle production, they brought advantages no competitor could match: controlled supply chains insulated from market volatility, proven battery reliability based on millions of units in the field, and manufacturing scale that had taken decades to optimize. Their two decades in batteries didn't just build technical expertise; it built proof. When automakers needed battery partners, BYD had years of safety data and proven manufacturing reliability. Their slow S-curve climb in one layer became instant credibility in another.

This pattern repeats. Mars didn't just buy Wrigley in 2008; they'd spent decades understanding confectionery economics. When Goldman needed capital, they called Buffett because he'd spent 40 years building both financial capacity and trust. The patience to understand which S-curve you're actually betting on, and when to be ready to pounce is what transforms good timing into inevitable 'Moat Expansion'.

How Trust Compounds Between Layers

Trust operates as time's ultimate multiplier - the one asset that compounds invisibly for decades then executes instantly when needed. While cash reserves show on balance sheets and infrastructure investments appear in CapEx reports, trust accumulates in the white space between transactions, in the consistency of kept promises, in the predictability of behavior under pressure. This is why Buffett could deploy billions with a handshake while others needed months of due diligence. Trust, carefully accumulated over decades, had compressed time itself.

This trust premium manifested dramatically during 2008. When Goldman Sachs needed capital urgently, Lloyd Blankfein didn't run a broad auction process - he called Buffett directly, knowing a deal could be struck in hours rather than weeks. When regulators needed someone to save Bear Stearns over a weekend, they turned to Jamie Dimon, whose decade-long relationship with the Fed had built unshakeable credibility. BlackRock's transformation happened because Barclays trusted Larry Fink to close a complex $13.5 billion transaction in the midst of market chaos. Trust, accumulated over decades, became the currency that enabled billion-dollar decisions in hours rather than months.

Warren Buffett's 2008 moves exemplified how trust operates across all three maps simultaneously. While others mocked Berkshire's growing cash pile - $40 billion sitting "idle" - he was building in the infrastructure layer (pace layers), preparing for the inevitable down-cycle in financial services' S-curve, and accumulating trust with every patient year. That cash pile represented more than financial capacity; it was trust crystallized into capital. Every year Buffett didn't chase returns, every quarter he resisted leverage, every deal he walked away from, he was depositing into an invisible trust account. When 2008 hit, that patient accumulation enabled lightning-fast execution: $8 billion deployed to Goldman Sachs with one phone call. The $7.7 billion total return exceeded Coca-Cola's entire 20-year dividend stream to Berkshire. Trust had compressed decades into days.

Jamie Dimon's insistence on a fortress balance sheet at JPMorgan seemed almost foolishly conservative during the boom years. But when Bear Stearns collapsed over a weekend in March 2008, only JPMorgan had both the capital strength and industry / regulatory trust to step up. They acquired $236 billion in assets for $10 per share - generating an estimated 1.5x return on their $8 billion all-in investment within four years from the prime brokerage business alone, while the strategic value of becoming Wall Street's buyer of last resort created competitive advantages worth multiples more for decades.

This wasn't casual or careless but rather the product of decades spent building trust, understanding the business deeply as it matured over time, and knowing what actually matters in a period of exchanging holders of the shares. This paradox of patient urgency runs through every successful long-term enterprise, manifesting as slowness in the deep layers that enables blazing speed in the surface layers when opportunity emerges. Be wary of ignoring, or no longer investing here over time.

The big open ended questions:

Pace Layers:

What layer am I in? (Fashion, Commerce, Infrastructure, Governance, or Culture)

What's the natural speed of this layer?

Am I fighting physics or flowing with it?

S-Curves:

Which S-curve am I actually betting on - the dying one or the emerging one?

Where is this initiative on its curve - early grind, inflection, or plateau?

What's building in other layers that could disrupt this curve?

Trust:

What trust am I building through this initiative?

Which stakeholder relationships will compound from this?

How does consistency here create future optionality?

The magic happens when you see all three maps aligning towards one direction of travel.

The so what:

Most strategic failures come from misreading one of these three maps as the ‘absolute truth’. This month, run your initiatives through all three lenses. The patience and urgency will sort themselves out once you stop fighting the system's natural rhythms.

But once you see it, you can't unsee it.

The companies that win the next decade won't be the fastest or the slowest, but those who understand which layer to push and when to wait, who build patient urgency into their organizational DNA, who realize that in business, as in nature, sustainable speed comes from respecting the rhythms of the system rather than fighting them. The river that carved the Grand Canyon started as rain. It understood something most businesses never learn: real power comes from patience, and the deepest currents move slowest but carry the most force.

Wow. A masterful exposition. I will be thinking about this all day. Thank you for writing on Substack.

Im curious if you think the graph of the S curve changes over time?

Im assuming that BYD may have thought that was the top of the S curve back in the day. But now looking back at this point in history you could graph it a completely different way. Its sort of like the S curve morphs and changes depending on when you look back. Like a river seen from a different bend—still flowing, but changing shape. What do you think?

Similarly Riva, the boat company that Eric Markowitz talks about, stayed making wood boats when fiber glass was probably the next s-curve. But staying true to their quality over time the wood boats are now highly valued. Is this just fashion s curves going from wood s-curve to fiber glass s-curve to back to wood s-curve? Or something different entirely? If feels different entirely for some reason. Or maybe if you can hold through fashion S curves until it reverts back to, in this case wood, it catapults your growth of a different s-curve?